Book 3: Chapter 3

European Craftsmen in New York City

The 1960’s in New York City were a whole different dimension in my life. Those years were not only about Kenneth’s Salon and its super rich clients, but some kind of energy in me that had always drawn me to the vibrance of art, artists and creativity – in any shape or form – gave way to another part of my life that was full of exquisite craftsmanship. Life itself is creative – and for me, human beings are at their best when they’re imagining something new, and making it come to life with their own two hands.

Sometime around 1966, I started developing an interest in wood carving. There’s something about working with wood that uplifts me, and brings out my inner artist. I don’t know if it’s the fragrance of the wood itself, the feel of the wood-grain under my fingers, or figuring out how to make the perfect dovetail or mortice and tennon joint. Every project is a journey of discovery.

Being able to look at a raw piece of wood and see what it could become – and then set to work turning it into a reality – was the best feeling in the world. To me, it was more than just an interest; I think I was falling in love with woodworking.

I found a master woodcarver from Sicily named Frank Lassitra, who could be found at a workshop in a loft on the Upper East Side around 66th and 1st Avenue. Whenever I got the chance, I would go there, and Frank would teach me a few tricks of the trade. He taught me about the incredible craftsmanship of 17th and 18th century, pure baroque woodworking.

The chairs, tables, bureaus, cabinets and shelves from that period were so intricate, and suberbly designed. I can’t find enough words to describe what a magical time that was!

The masterpieces from that age radiate a luxurious sort of feeling – every piece is richly decorated with inlays, curls, carvings and gold-leaf. You simply don’t find that kind of craftsmanship and attention to detail anymore – only in antique shops, and only if you’re lucky.

The masterpieces from that age radiate a luxurious sort of feeling – every piece is richly decorated with inlays, curls, carvings and gold-leaf. You simply don’t find that kind of craftsmanship and attention to detail anymore – only in antique shops, and only if you’re lucky.

As I worked at my bench, I was learning patience and dedication. I learned to go with the grain of the wood, feeling what the living material wanted to become. I learned that if you go against the grain, you ruin the carving, and hurt yourself in the process.

Frank would come over and show me where I was going wrong, and give me a few tips, and then go back to his carving again. It was a wonderul feeling to just get lost in the craft and feel my hands warm and tingling afterwards; I would end up covered in sawdust and shavings, and somehow that felt so rewarding.

Learning the Craft, Living the Life

During that time I had the privilege to meet a number of amazing craftsmen. There was a man from Brazil who could do the most amazing gold-leafing on glass. I also got to know James Capovan, who became the mentor and great-grandfather I never had. Even if I was only in my twenties at the time, and he was already in his eighties, we hit it off famously.

James was a man of many talents; he taught me so many things about work and life. He loved what he did, his craft was his life, and those hands of his could do anything. He never missed a day of work, and he was never out of things to do. To this day, I still remember him proudly saying, “I’ve never been out of work for a single day in my entire life!”. His skill, his craftsmanship, and his strong work ethic sustained him through the Great Depression, recessions, and both World Wars. No matter what was happening, his willing hands would always put food on his table.

James was a master goldsmith, silversmith and metalsmith who had come from Venice. He knew many things about art and culture, and he had the street-smarts to match. A craftsman, a street urchin, and a rare character! When I was around him it was as if I was basking in the light of his deep life-knowledge, and I was so grateful to be absorbing it all. I was lucky to have met Jimmy.

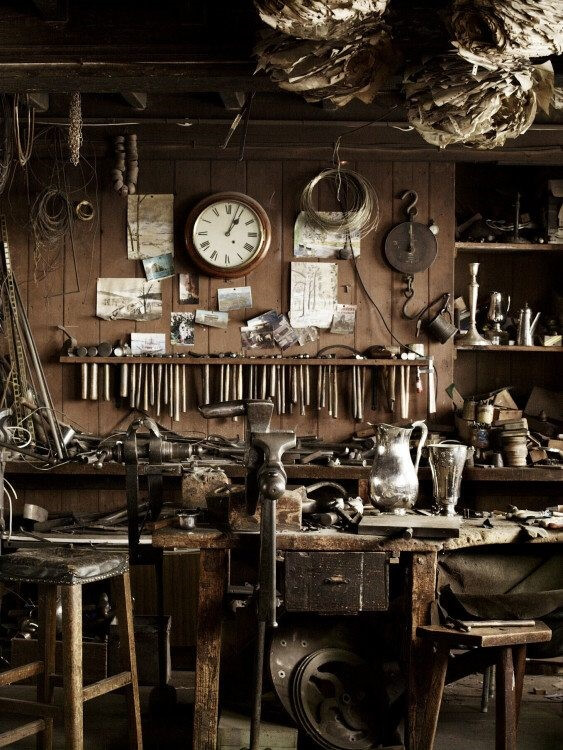

We decided to start our own little enterprise – a workshop, gallery and shop. Call it coincidence, or call it synchronicity – but we found the perfect spot for it on East 77th street, right across from my apartment. I ended up becoming the business manager, and James continued doing what he did best: state-of-the-art crafts. He moved into the basement and set up his workshop, where he had apprentices coming from Canada and all across the United States. They had come from far and wide to learn and work in the worshop. You could hear them all day long banging on copper pots, re-tinning them and creating beautiful artwork out of the scrap we found lying around.

We found amazing treasures in the trash heaps on Park and Fifth avenue. Early in the mornings, we’d sift through the trash, and find old, broken furniture and cast-away household items, even works of art that were near-ruined.

We found amazing treasures in the trash heaps on Park and Fifth avenue. Early in the mornings, we’d sift through the trash, and find old, broken furniture and cast-away household items, even works of art that were near-ruined.

We didn’t mind – with the skills at our disposal we could restore them, good as new. A little bit of imagination, lots of know-how, some hard work… And presto! Something new and beautiful out of something old an abused.

In our company, there was also a Czeckoslovakian man, Tony Merka, who was a genius at mixing paints. He had an incredible knack at restoring the canvases we found. He was so talented that he could bring any artwork back to life again, no matter how dirty, ripped or spoiled it was. We dragged all the trash back to our little workshop, and – like magic – we would create things of beauty.

We named our business European Craftsmen Limited – and it was a success. More and more apprentice workers got to know about us, and they wanted to come study under the master. When they were finished with their training, they went off and started their own businesses. We trained jewelry makers, furniture restorers, painters, carpenters, and entrepreneurs. I learned so much about arts and crafts during that time – and gained a world of understanding about antiques too.

In 1969 we were able to take part in an event sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation called Forging a Nation. James became one of the featured artists. During that event, limousines would arrive in the morning to take him to the show, while trucks picked up the tools and workbenches, and carted them off to the Rockefeller Center. We made the news, and they even featured us on television channels, such as CBS, NBC and ABC. They all ran a story on “James Capovan, the master metalworker from Venice.”

Those Were the Days

To be honest, I don’t know how I managed it. I had to run the business in my spare time – and there wasn’t very much of that. Most days I would get back from work at Kenneth’s at six or seven in the evening, and take a nap until ten or eleven; and then, after a quick shower and shave, I would be back at it again. If I wasn’t at the workshop, I was at the clubs. In ten years of New York life, I don’t’ think I ever slept – I must have survived on naps only! Life was just too exciting for sleep.

In those years you could go out to the cafes like The Kettle of Fish, White Horse Tavern or Gas Light; or to the discos in Greenwich Village and catch performances by Barbara Streisand, Mary Hopkins, Tony Curtis, or any number of up-and-coming stars. The folk music scene was famous too. It was a melting pot and an artist’s canvas of a brand new world culture. The Mary Hopkins hit song from 1968 springs to mind:

“Once upon a time there was a tavern

“Once upon a time there was a tavern

Where we used to raise a glass or two

Remember how we laughed away the hours

And dreamed of all the great things we would do

Those were the days my friend

We thought they’d never end

We’d sing and dance forever and a day

We’d live the life we choose

We’d fight and never lose

For we were young and sure to have our way

La la la la…”

It was a time like no other. The culture of Greenwich Village, the bohemians, and the energy of New York… The adventure of a lifetime! There I was, burning the candle at both ends, hardly getting any sleep, and studying the lessons of the University of Life.

It was also during this time that I met two amazing people who became my ‘adopted’ parents, Bernie and Evelyn – and that’s the story I want to share in the next chapter.